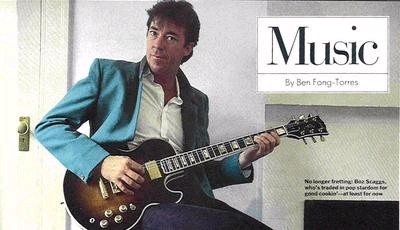

GQ Magazine - Boz Scaggs Interview

[By: Ben Fong-Torres - 1984]From the files of Boz Friend SusanBoz Scaggs Searches For The Perfect Fried Chicken (Catching up with that well-known restaurateur whose new album, he keeps insisting, is coming "any day now".) This isn't one of those "What ever happened to?" pieces. Those are about has-beens, and Boz Scaggs, whom you remember for "Lowdown," "Lido Shuffle," "Jojo," "Breakdown Dead Ahead," and "Look What You've Done to Me," is still making lots of music. Trouble is, the music he's making these days is playing only on the turntable of his mind. Since 1980, there's been no album from Boz. Except for three songs, including one ("Miss Sun") to fill out a greatest-hits album and another to help his manager complete a movie soundtrack, he's steered clear of recording studios. He's appeared more often in local blues clubs for impromptu jams than on concert stages. And he hasn't toured at all. This – and no more – from a man who worked ten years to achieve success, who earned millions of dollars and became a darling of the critics. After he performed a ballad at a fund-raiser for the San Francisco Opera in 1982, the morning paper's arts reviewer gushed: "Boz Scaggs?may be the finest popular singer to come along since Frank Sinatra. He's certainly the sexiest." Around San Francisco, there was plenty of gossip about what ever happened to Scaggs. Around the time of his last album, "Middle Man", he was separating from his wife of eight years, Carmella; it was not a pleasant splituation, as Herb Caen, the local pundit, would put it, there being lots of money and two kids involved. Carmella, a bright, stunning woman, was high on society, and her energetic ladder-climbing was well documented by an adoring black-tie press. Boz, in the meantime, was seen here and there, hosting a symphony benefit or smashing up his motorcycle, attending a ballet performance or getting into a drunken brawl. Through all the gossip, the question was: When would he put out another album? I ran into him a couple of years ago and asked about his next record. His "any day now" reminded me of the response you give a bill collector making his third call. Nonetheless, Scaggs is doing fine now, thank you. He's got joint custody of his two young boys. He lives in a comfortable eight-room home in the best part of town. He's in love with a beautiful young Frenchwoman and seems reinspired musically – at least enough to turn his dining room into a modest sixteen-track studio. And he's opened the Blue Light Café, a restaurant serving the cuisine of his native Southwest: chili, mesquite-grilled ribs, chicken-fried steak, hush puppies and fajitas. But he'll be the first to admit that he's been through some major middle-age craziness and that, at age 40, he's "semiretired. I guess this is a "What ever happened to". Not about a has-been, but about a performer whose greatest musical achievements and greatest domestic failure came hand-in-hand; a musician who found that success had a way of imposing estrictions instead of delivering him his freedom. Scaggs, it should be noted, has never been at ease with the celebrity most performers aspire to. Born in Ohio and raised in Dallas, he is almost painfully shy and seemingly irritated by public attention. He understands the need for occasional press, but acts as if he were being grilled when talking about himself. You can nearly forget you’re talking to a consummate performer and musician who blends an onstage charm that captivates women, a deeply soulful way with a song and a talent for writing music – much of it in the studio under deadline pressure – that is as clever as it is elliptical. In his living room, he huddled against the corner of his sofa and lit up a Marlboro before he talked, in a barely audible voice, about his retreat from music. “I’d been working very hard since putting my band together in San Francisco,” he began; I enjoyed it but after ten years of the routine of make-a-record-go-on-the-road, I found myself using up a lot of time and energy with things that weren’t so important to me, the things it takes to maintain a high-level career. It was taxing my physical and mental being too much.” By 1980, a number of significant things had happened to Boz. He had shed his early identity as the guitarist behind the Steve Miller Band; he’d become a favorite on FM radio, especially for a euphoric blues number called “Loan Me a Dime.” With help from Carmella, he'd staged a series of New Years Eve concerts in Oakland at the Paramount, a beautifully restored art deco movie theater. Besides his band, a thirty-piece classical orchestra came along; symphonic soul, it was called. His music moved into Motown and Philly turf. In the midst of the disco rage, he sold some 7 million copies of Silk Degrees. He and Carmella had their two boys. There was a breakdown dead ahead. We had two children,” said Boz. I wasn't happy. He smiled at the irony, thought for a long moment and explained: That was the thing that divided us, as opposed to the way you'd think it would work. During the Paramount Theatre years, Carmella was widely credited with the makeover of Boz’s image, from sweaty-haired, golf-shirted country-blues guitarist to tuxedoed, blow-dried crooner. She classed up his act. She was right there growing with me,” said Boz. “She helped shape my career. But I think she lost interest. I made an attempt for a year?but we weren’t talking. I'd take her out to a restaurant and find I was talking to a person I didn't know. In 1980, he put out Middle Man; and separated from his wife. It all came to a head. I had to deal with the realities, the legalities of the divorce and the emotional changes. That was coupled with the fact that I had been touring a lot, had been in the studio and been away, and I was tired of it. My boys were two and three, and they had their demands. Being away two or three weeks at a time, I was missing a good deal of being a parent. Over the next three and a half years, he and Carmella fought for custody of the boys. The bitter proceedings kept him in San Francisco and partly explain his musical lethargy: Had Boz relented and left the boys in his wife’s custody, he would have been able to move to New York and immerse himself in the music scene. Instead, he’s got the kids for the summer. While a governess watched them, we had lunch at a nearby seafood restaurant. “I really feel no pressure to make a record,” he said. “In one way I feel guilty, it’s a shame to let a career I worked so hard to build, and that people seem to appreciate – it’d be a shame to let that go. I don’t feel that I am, but I don’t know an honest way of getting what I’m doing now out in public. I don’t want to go on the road, and I don’t want to go into a studio now. I have things to do here; I have responsibilities. Besides his kids, he's got the restaurant. It's the result of a long-held interest, dating back a dozen years or so. Scaggs has always enjoyed cooking, but he's vague about why he wanted to open his own place. Lots of friends in the business; lots of talk about restaurants and food?It's another experiment, a challenge? Boz Scaggs is making a rare appearance in the Blue Light’s kitchen. Through the plate glass, early lunch patrons spot him and ask the waiters what Boz is up to. He’s onstage again. Two months after the Café’s opening night, he’s still trying to get the pressure cooker to make fried chicken the way he wants it to. Until he gets the batter’s consistency and texture just right, he says, fried chicken will sty off the menu. The recipe is one he came up with during Sunday-evening experiments, after coming home from recording Middle Man. Today he tries various ratios of the seasoned flour and buttermilk garlic batter; he tries bread crumbs, he tries different cooking times. He works for almost an hour, dipping, frying, waiting, tasting. While he experiments, I try some chicken-fried steak that doesn’t remind me at all of the tough stuff I used to eat in Amarillo. When I’m finished, Boz sits down and lights up a Marlboro. “Yesterday,” he says, “I got an hour and a half to go down to the dining-room studio. It was like a luxury, to have time when the kids weren’t there. I didn't realize how precious that time was. In the studio, he says, he's playing some blues, some R&B, and some progressive, groove stuff. But it’s basically the music I know.” Boz has recently been searching for a copy of Jimmy Reed’s “Going by the River,” a song he remembers from his childhood. “It’s one of the most beautiful blues pieces I’ve heard. I want to record it.” But he’s in no hurry. He’s busy with travel and the restaurant through August. “Maybe I could get started in September,” he guesses without an ounce of certainty. I have things to do here,” he says once more, as if to remind himself. And with that Scaggs takes his leave, back to the kitchen’s spotlight and his meditations and improvisations on fried chicken.

|

|||||||