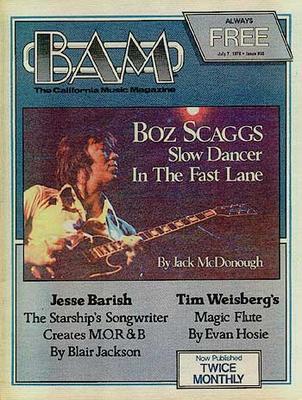

Boz Scaggs Interview - BAM Magazine July 1978

Boz is San Francisco’s missing link between the bluesdelic ‘60’s and the fashionably late ‘70’s. How many other musicians whose singles get the grooves played off them in every disco in the country could make it through a night playing T-Bone Walker shuffles and Freddie King blues if he had to? Boz himself recoils at the thought that anyone would consider him a disco artist, just as he recoils from the off-hand classification of his work as “blue-eyed-soul.” Still, it is true that a tune like “Lowdown,” from his fabulously successful Silk Degrees album – the album that made him a national star – brought missing muscle to the disco sound. No dancer could ignore the sleek and silken groove set up by “Lowdown’s” burping bass intro, and many times I’ve seen a visible snap go through a dance crowd when that tune came on. Yet no one, no matter how deeply a dyed-in-the-wool Dead or Airplane/Starship fan, no matter how suspicious of the superficialities of disco music, could point a finger at Boz. Everyone knows he was there back in the beginning, when he and the rest of the original Steve Miller Band were blowing the doors off the old Fillmore with the restless blues they had brought out from Chicago and Madison. Boz crossed over from the old world to the new four years ago by creating, almost single-handedly, a whole new style of concert-going, just after the release of Slow Dancer – a watershed Scaggs album even though it sold only about one-tenth the quantity of Silk Degrees. It was in March 1974 that Boz contracted the Paramount Theatre in Oakland (which had not been used before that for rock, and which Boz described then as “a time capsule into the Thirties”) for three consecutive nights of “formal-wear optional” concerts with Boz’s band augmented by a thirty-piece mini orchestra. It was a sensational idea that immediately captured the imagination of many a concert-goer, and established a style of after-dark activity that gave the San Francisco rock and roll culture a dramatic new tone. Boz followed up with lavish multiple-date Paramount performances for three years in a row during the Christmas-New Year’s holiday season, and everyone else in town picked up the cue. Every invitation you now see that reads “a dressy affair” or “dress code of casual elegance” or “class rags suggested” is a descendant of those first Paramount dates. But most important, those pioneer gala affairs proved to be a precisely accurate presaging of the smooth-stepping highlife style that Travolta/Bee Gees fever has institutionalised as the touchstone of late 1970’s pop culture. In fact, save for the recalcitrance of Boz’s record label, Columbia, “Lowdown” would have been on the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack – a fact which Boz reveals with a bit of a groan as he considers the royalties on 12 million units. As much as anything else, those staggering sales figures prove that it is indeed a new world, and Boz who has moved carefully with the changes, is part of that world. By doing three successive years of such highly-anticipated New Year’s Eve shows, Scaggs became the Guy Lombardo of San Francisco hipdom – again, a characterisation from which Boz would recoil, but which in the realm of metaphor is nonetheless true. Another such analogy might be made to Frank Sinatra, because Boz, as much as a rock and roll star could be, is his contemporary equivalent: a suave, handsome, sharply-dressed singer of orchestrally-bedded love songs that have immense across-the-board appeal. And, like Sinatra, Scaggs reinforces that allure with a dramatic and tangible sense of charisma. The Scaggs charisma flows naturally from Boz’s highly developed sense of style as well as from an equally developed sense of order and balance. His stylish sensibilities are immediately apparent in both the richly-layered romanticism of Boz’s music and in the manner of its presentation. The Starship may have made the move into the late ‘70’s by shifting away from politics and sci-fi, and writing solid rock and roll love songs; Steve Miller may have made the move by evolving his space-cowboy persona into that of the consummate studio craftsman who could make records so exhilaratingly bright and spacious that no one could resist them; and the Grateful Dead may have made the move by finally getting smart enough to work with a producer who could take their awesome playing talent and mould it into something more elegant than even the Dead would have suspected themselves capable of. Nonetheless, they and most other San Francisco bands still look pretty much the same as they always did; still appearing in jeans, scruffy boots, and other elements of casual attire. Meanwhile, Boz is on stage in crushed velvet jackets and white-on-white sports outfits, performing in front of a tuxedoed-and-gowned string sections. So there should be a little sense of mystery as to why the Dead, while they may still be deified in some San Francisco quarters, don’t cut it out in the heartland of the state where the warm-weather suburban baby dolls just love Boz to death. Of course that sense of style finds many other forms of manifestation. Scaggs’ Pacific Heights home – his third successive residence in The attic is Boz’s practice room. It would be a sacrilegious understatement to describe this room as an inspirational place to create music; looking out, at that height, upon the Bridge and the Marin headlands and the mighty Bay elbowing its way among the islands and peninsulas north of San Francisco, is like looking out into Middle Earth. The room is uncluttered – some large speakers, taping equipment, a stunning custom-made LS5 guitar (“I had just about given up on Gibson,” says Boz, “until they sent me this,”) and an electric piano, the instrument Boz prefers for skeleton melody work. “There is a gut thing about sitting at a piano with your fingers on notes that you can literally see. The guitar I think is more of a mood instrument. I sense moods that come off it. But there is a different sense of resonance and depth in the piano. The actual textures of the piano lend themselves so much to the human voice.” The choreography of the house reflects not only Boz’s general social temperament – most everyone who meets him notes his gentlemanly demeanour and considered approach to all matters – but also his general psychic balance and his philosophy of order. Anything that might fall under the categorical heading of “God,” he agrees, has something to do with an order in the universe to which one might learn to attune oneself. “The word ‘God’ is so hard to get through,” says Boz, “that I don’t even find it in my vocabulary. I find no consolation in the traditional concepts of heaven and hell and don’t relate to that at all. But I do feel there is some sense of order in the universe. There are some truths – although I couldn’t give you any – and there is order. You know it when you are in touch with it. I’ve met people of a high spiritual nature and there is something about those people that’s good and right and truthful… a timelessness.” That appreciation for a perceived but unknowable sense of order extends into and affects other areas of Scaggs’ life – and no doubt makes him quite a different person than many fans might think him to be. Boz has not, for instance, eaten meat for 11 years, save for one incident almost five years ago. The non-meat diet traces back to the mid 1960’s when he was living in Europe and, for a short time, in India. “I just lost my taste for it. The idea of killing animals was part of it, and still is. I just don’t see any need to slaughter animals. I’m not idealistic or religious about it, but I don’t see the need for it.” He meditates, but, he explains, “not as an active process. I can sit down and listen to a record and go completely beyond myself. I can’t remember anything afterwards. I can play piano for ten minutes and be totally into it, be completely clear, in a state where there’s nothing in my mind. “Meditation and yoga are very powerful stuff, and I think unless there’s a very firm basis in the person’s state of mind, unless the goals are pure and open and very carefully chosen, there is a danger of distortion. But it’s good that more and more people are becoming aware of these various methods of self-improvement. It’s an open secret now that life is just full of way-out goodies.” During the past 6 months Boz has been able to spend more time than usual enjoying his house. Down Two Then Left was released in December (it entered the charts at #26, and pulled Silk Degrees, which had fallen to #116 after 90 weeks on the charts, back up to #74). But even though there was a new album Boz decided, for the first time in four years, not to do the Paramount New Year’s dates. “It had become too hectic. I had just come back from the road and didn’t have any ideas together, and I had promised myself not to do it again unless I had something very special to offer, because it had become too routine. It was also the first Christmas for my new son, Oscar, and so we spent a traditional holiday. But a lot of people did ask, a lot of people were disappointed, and this year I expect to do those shows again.” After Christmas Boz made a tour swing through the South which brought him into states like North and South Carolina, where he had never played before. Then in February he went for the first time to the Far East, playing dates in Japan, New Zealand, and Australia. This was a signal event in his career, of course; a Far East tour is an immensely expensive proposition and no performer who has not achieved a substantial level of sales makes such a tour. He had reached that level with Silk Degrees, which set a record by remaining on top of the Australian charts for 22 weeks, and Boz indicates that “two major promoters went back and forth in a bidding contest to get us over there. “I had very few preconceptions about Japan or Australia. Of course Japan is a favourite place for musicians because you’re playing for an audience that’s very up on American styles and that’s devoted and appreciative. Other audiences can’t compare to the Japanese just for sheer attentiveness and appreciation. I think it’s in the nature of the people, the singlemindedness toward everything they do – their family life, their jobs, and their culture. Since returning from Japan and Australia, Boz has had a chance to assemble thoughts for the always-awaited “next album” which, most likely, will not appear for at least another six months. As well as being a Slow Dancer, Boz is a slow worker, a tinkerer, and a perfectionist who will take all the time necessary to be sure something is right. “I’m now just starting to get back into it,” he explains. I was really glad to get out of the studio last time. I just wanted to get out, to get some vacation time, and to give myself some time away for the first time in years. So just now I’m back at the point where I can sit down at the piano and work on things, and I’m getting excited about it.” Boz’s method of working is intriguing. “I conceive of a song first of all in terms of musical feel and tempo. I have a list now of 14 song ideas, but I’m not sure of anything in terms of specifics. I haven’t written the tunes, they’re not on tape, but I know the kind of material I want. “For instance, on the list there’s a reference to a particular song Thom Bell did with The Spinners about three years ago. It has a great tempo and I haven’t heard anybody else use it. Since I heard it, I’ve wanted to write a song creating some chord changes to that tempo. Every time I heard the song I’d remind myself, ‘I’ve got to get to that.’ So by the time I did sit down with that tempo I’ve thought about it a lot – whether it will be two or three chords or nine or ten, can it be minor or major, where the bridge will be. I’ve imagined it out, sitting on airplanes thinking about that tempo. So what it amounts to is sitting down and pumping some life into it and giving it some form, and it will probably emerge as a song.” Another integral part of the Scaggs method is to leave the lyrics until last and to do a lot of work right in the studio – which is why he has such a predilection for highly accomplished studio players. Writing the words, explains Boz, “is the real tough part for me. It’s the part I always put off until the last minute. It’s like a reporter meeting a deadline or someone cramming for an exam. It comes down to the last minute and to those chemicals of adrenaline and fear.” It was exactly one of those situations in 1973, during the recording of Slow Dancer that precipitated his unusual decision to break from his vegetarian diet. “I was very frustrated at one point during the making of that album. Couldn’t write, couldn’t think. So I decided to do something to jolt myself, and I ordered up the biggest steak I could get from room service. It took me about three days to digest it, but then I ate meat for about a month. There was a great change in my disposition. My system was wrecked. I got very aggressive, short-tempered, on edge. Then I stopped, and within two or three days I was myself again. I haven’t eaten it since. I think it’s obvious to anyone who experiments that if you don’t eat meat you will feel different.” As for waiting for the pressure of the situation to force out the right words, says Boz, “Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. I’ve been disappointed or embarrassed three years after an album’s been made, and I’ll go back and listen and wonder where something came from because it sounds trite or stupid. But then I really don’t know anybody who does it – who takes finished material into the studio. Paul Simon might, or maybe Brecker and Fagen of Steely Dan. “The thing is that working off the cuff with the musician’s right in the studio gives you a lot of freedom to spark something. I’m constantly inspired by the musicians who become available to me as time goes on – the way they develop ideas, the pride they take in their individuality. They bring a great vitality to the session because they can understand complex ideas. They come in when the clock hits the hour, but for that time while they’re in there, anything goes. They’re used to getting way-out stuff thrown at them and they’re real loose. If you give them their head to use their ideas and to play their ‘A’ chops, you’re going to get some real good stuff, some way out sounds.” This respect for the benefits of an alliance with professional studio players goes back to his early sessions in Muscle Shoals, Alabama (a famous rhythm and blues recording centre) where Boz cut his first solo album as well as half of his fourth album, My Time. “If one word can characterise Muscle Shoals,” said Boz after My Time’s release, “it’s spontaneous. We cut thirteen tracks in two days. Tracks that were only sketches, brief ideas in mind when we started, materialised in half an hour or 45 minutes. For both ‘Dinah Flo’ and ‘My Time’ there was absolutely nothing conceived, no words even, before I sat down to sing. I knew what the vocal line had to sound like, so I’d just sing to the rhythm. “It’s not so unusual a way to work as you might think. But that’s the sort of thing Muscle Shoals inspires. Those musicians can develop a thought instantly, they can carry it out to its fullest extent and then run through variations of it. That would take hours, days, even weeks under different circumstances.” Again, after making Slow Dancer with Motown players like James Jamerson and Davit T. Walker, players whom Boz says he had idolised for years, he remarked, “They’re geniuses. But it’s the behind the scenes part of the business, and people don’t recognise how incredibly brilliant these people are. They’re so confident in their abilities that you can give them an idea or a feeling, and they can sense the song and play it back for you. That blows me away.” Boz’s love for working with such players sometimes runs counter to another desire to maintain a regular working troupe. “I had thought after Silk Degrees that I would be able to take those players out onto the road with me. Elton John had that situation and it provides a great deal of flexibility. If you have an idea for a tune you have the fellows right there with you and you can develop it during a rehearsal or a sound check, or maybe everybody takes a vacation for a few weeks and goes some place where there’s a studio. I thought I had that in hand with the Silk Degrees players. But they’re primarily studio players with their own careers to look after and ultimately it didn’t work out. I still think that would be a good situation, and I may be able to work it out with the musicians I have around me now. But you always have to be aware that when you have a permanent band, there’s the danger of the ideas getting permanent.” Boz is spending late spring on the road, but he will be finished by the Fourth of July, in time for the birth of his second child. Boz was born William Royce Scaggs in June, 1944 in Ohio, where the family remained for a year and a half. Most of the next 8 years was spent in Oklahoma. Because of his father Royce’s military affiliation and the sales occupation, there was some moving about in that time, after which the family settled in Plano, a Dallas suburb. The name Boz “is a contraction of Bosley, a weird nickname given me when I was about 14 and started going to a new school.” Though he had brothers and sisters, Boz remembers, “When I was a kid I spent a lot of time exploring around the woods alone. I always felt close to nature, and I sense things intellectually that I haven’t been taught.” When he was 15 he met Steve Miller at school in Dallas and was asked to join Miller’s band, The Marksmen, as vocalist and tambourine player, while Miller taught him rhythm guitar. Boz’s first guitar was a 1952 Epiphone (“It was called a Zephyr or Casino, I think.”), and he moved on to a Gibson 170, and later to a big Gretsch Country Gentleman. “The sound we were getting off on in those days,” says Boz, “was T-Bone Walker, Freddie King and B.B. King. Walker was my earliest influence and the guy I sat down and learned a lot of stuff from, and he always played a hollow body guitar. That was the sound of the blues. B.B. King played one too. Chet Atkins had a strong influence on me, and Jim Hall also.” Miller, who was a year older, finished school before Boz and went up to the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where Boz went a year later to join Miller’s band, The Ardells. Then Boz went back to Texas to form an R&B band, The Wigs, and in 1964 that band went over to England to find fame and fortune. What they found was an overload of R&B bands on the circuit already. The others came back home, but Boz stayed on to roam around Europe as a folksinger, and in Stockholm he cut an album for Polydor called Boz that was released in Europe alone. During this time he travelled to India, a journey which served to change some of his attitudes toward the spiritual concerns of life. One Day in Stockholm Boz got a postcard from Miller, who by this time had left Madison, paid some dues in Chicago as part of the Miller-Goldberg Blues Band, and migrated to San Francisco to found a band. He wanted Scaggs to join. Boz came back in 1967 and with the Steve Miller Band cut Children of the Future and Sailor, two beautiful albums which plugged directly into the Promised Land psychedelic fantasia of the time. Remembers Boz, “To a great extent, Steve did his songs by himself and I did my songs by myself. I didn’t play on ‘Livin’ in the U.S.A. or ‘Sweet Mary’ or ‘Quicksilver Girl.’ Steve didn’t play on ‘Dime-A-Dance-Romance’ or ‘Baby’s Calling Me Home’ or ‘Overdrive,’ although he did play lead on ‘Stepping Stone.’ Se we were working on our own things even when I was with the band. After Sailor I wanted to continue recording my own songs.” So Boz left the Miller band and with some help from neighbour Jann Wenner, publisher/editor of Rolling Stone, secured a deal with Atlantic and went to Muscle Shoals to cut an album which Wenner produced. This was the beginning of a very ambivalent relationship with Stone which continues to this day. Stone has both features him on the cover in glorious colour and run photos of Boz stretched out cold on the concrete outside an Austin nightclub, where he had been laid low by a punch from a backstage guard in a drunken misunderstanding. Boz’s present attitude toward the press in general is cautious. “As the career goes on the plot thickens, and distortion by the press does increase. As you become more of a public figure you become subject to more subjective analysis and things get pretty way out sometimes. In the old days, if someone came to you, you could be a little more certain that they had a genuine interest. Nowadays, people seem to take a different attitude. The Eastern pop music press particularly. It becomes disheartening to give a serious answer to a question and see it come out distorted and twisted. It seems they just use the words to make a point that they want to make. It seems a lot of pop music reporting is done more to satisfy the needs of the writer than the audience. I haven’t much respect for pop music writers anyway. I’m always interested to read what various critics have to say. I appreciate finding someone who has a good sense of history and who can take an album seriously from a musical point of view. But I think a lot of it is pretentious crap. “It’s like the phrase ‘blue-eyed-soul.’ That’s always been a curiosity to me. I can see where people would coin such a phrase. But I take it all more seriously than that. Because I know that the producers, arrangers, and players have a very high level of both musical awareness and competence. So I don’t take those catch phrases into account unless the writer takes such things into account – who the players are and what they’re doing, and chord structures and so on. It’s true the term was interesting a while back because you had the phenomenon of Bowie crossing into the soul charts, and Elton had a hit, and Hall & Oates were also on the black charts. But it’s just a term, just a phrase.” The Muscle Shoals sessions resulted in a piece of vinyl manna that was ignored everywhere else in the country except San Francisco, where it has never really been off the airwaves (“Loan Me A Dime” from that record ranks as KSAN’s all-time #1 song). In Muscle Shoals Boz had that first taste of session men who could do anything – Barry Beckett, David Hood and Roger Hawkins among them – and he foreshadowed the future by using horns and backing female voices. He also used the services of one Duane Allman (of Allman Brothers Band fame). “When Jann and I were putting together the album, we listened to everything we could get our hands on that had been cut in Muscle Shoals. We listened to anything Duane Allman had played on. We didn’t know who he was – he just kept popping up on those albums – and we said, ‘Can we have Duane Allman on the sessions?’” The album that followed was Moments (recorded at Wally ??eiders Studio with Glyn Johns producing) which contained Boz’s first semblance of a hit, “We Were Always Sweethearts” as well as exquisite compositions like “Near You,” “Painted Bells,” “We Been Away,” and “Can I Make It Last.” His next, Boz Scaggs and Band, was recorded mainly in London, again with Johns, and contains “Running Blue,” which still shows up in live performance. Boz continued with the aforementioned My Time, which contains the exceptionally poetic “Slowly in the West” as well as Al Green’s “Old Time Lovin’,” Allen Toussaint’s “Freedom For The Stallion” and the two much-loved rockers, “Dinah Flo” and “Full Rock Power Slide,” which Les Dudek used to play the shit out of when he was with Boz’s band. For these three records Boz relied mainly on a core of San Francisco players that included drummer George Rains, bassist David Brown (writer of “Slowly in the West”), guitarist Doug Simril, keyboardist Joachim Young, and horn players Mel Martin and Pat O’Hara. Then came the change. Boz had been toying with the ideal of going to Philadelphia to work with Gamble & Huff or with Thom Bell, whom he considers the most important figure of 1970’s music. “He took us out of the Sixties. He was very influenced by the Burt Bacharach-Hal David style of writing and the Henry Mancini style of arrangement. He put that together with these fantastic rhythms that were already running around the streets of the ghettos, and he came up with this package and this style of music that isn’t going to be duplicated. Very important American music came out of that period – real, new, and innovative stuff. That for me was the major movement of the 70’s.” But while Boz was thinking about Philadelphia, an idea came down through the Columbia A&R department for a Motown-styled album, and Boz discovered that the great Motown players like Jamerson and Walker were available in Los Angeles. So he teamed up with producer Johnny Bristol, who in 12 years at Motown had produced hits by Gladys Knight, The Supremes and Junior Walker. Bristol signed up the players as well as arranger H.B. Barnum, who had been working with Lou Rawls, among many others. It was a different way to work. Boz and Bristol put material together, sang it to each other, and while Boz went back to San Francisco, Bristol called in the session men to lay down the tracks. Then Boz came back in to sing. Horns, strings, back-up voices, and adjustments were all added later. His new role as “only a singer” required a considerable adjustment. “I started to feel insecure,” recalls Boz, “and felt great frustration several times because of difficulty in writing things. I had a feeling that things were getting out of proportion. It was frightening at first until I realised that it was just a whole new thing. I was learning how to sing, how to use my voice, and how to use dynamics. I really had to live up to those tracks.” So it was that Boz became a singer and ultimately an orchestra leader, and in the process gave a new dimension to San Francisco – and California – music. (Even as he solidifies his identity as a vocalist, Boz’s talent as a songwriter is certified by the appearance of his tunes on albums by other name artists. Rita Coolidge has included “Slow Dancer” on her most recent release, after having a hit single with “We’re All Alone,” a song also covered by Frankie Valli.) Since Slow Dancer Boz has maintained the pattern of recording in Los Angeles (with players called together by Joe Wissert, who produced both Silk Degrees and Down Two Then Left). And Boz has proved more adaptable than anyone else in maintaining a base identification in San Francisco while making full use of the resources of the Los Angeles recording scene. Boz’s early break with the Steve Miller Band even after two such excellent albums as Children Of The Future and Sailor, was a clear indication of the independence he would manifest in all his affairs – from his experiments in recording in wildly varied locales with a string of different producers, to his seemingly organic resistance to a long-term band; from his distaste for working with Bill Graham, to the fact that he managed himself for three years. The problem with Graham dates back to 1972 when the movie Fillmore, an account of the Carousel Ballroom’s final days, came out. During one scene in the movie Graham claims that Boz, after hassling to headline a show, wanted to change his billing so he could catch an earlier plane to New York. “That was a lie, a total fabrication,” said Boz at the time. He was equally incensed about Graham advertising his name before agreements were confirmed, and for not being candid about the facts of the filming and recording. “He’s got a full sound crew, engineer, 16-track recorder, mikes all wired up to the Fillmore sound system. Thirty minutes before I went on, he sent someone in to have me sign a release for anything he might record there. It was totally absurd. I’d spend months in a recording studio to make a good recording, and now Bill Graham wants to record my performance and put it out on an album. It’s Bill Graham the amazing rip-off artist, ripping off everybody in sight for anything he can get from them.” As a result, Boz is the only major San Francisco musician who does not automatically play for Graham. Over the years he has worked instead with such concert producers as Bill Ehlert (a.k.a. the Jolly Giant) and Morning Sun Productions, and he has had his own organisation produce all of the New Year’s Shows. Graham did not produce the March 1974 Paramount shows, and Boz played a Day on the Green in 1976 – less than a year after he had almost had a public fist fight with Graham – substituting for the Starship who had unexpectedly pulled out of the date. As to why he performed on a Graham show then, Boz explained, “It wasn’t a matter of morals. I wasn’t playing for Bill Graham. It was a business affair. I wouldn’t like my fans to go out and endure the discomfort of that sort of show. But I didn’t feel it was my responsibility. It was the Starship’s show, and I was put on as a matter of convenience. I don’t think I’d have done it if I had been approaches from the beginning, because that’s never been my criterion for shows. I’ve never played in San Francisco just to draw as big a crowd as I can. Nonetheless, there was a good deal of money involved which insured that we could go East and play some festival shows there. And I didn’t know if I could go into a situation like that and project that material to a crowd that large, and I felt very good about it afterward. “As for Bill Graham and myself, we spoke for maybe one minute that day. I’ve always felt that the deals I’ve had with him in the past were one-sided in his favour. But he’s never cheated anybody that I know of. I wouldn’t go out of my way to do any harm to Bill Graham, or to anybody.” (Graham had little to say in response, mentioning only that he thinks that “Boz Scaggs is a great artist,” and that he is “looking forward to working with Scaggs again.”) But perhaps the greatest evidence of Boz’s fiercely independent streak was his three-year period of self-management. Now, of course, he is managed by Irving Azoff, whose name is so well-known in the industry (The Eagles, Jimmy Buffett, Dan Fogelberg and Steely Dan are his other clients) that even people who don’t know him use his first name as if they did. Scaggs’ first management contract was with Schiffman and Larson of Los Angeles, with whom he remained for a year and a half. “But in fact,” he says, “we stopped communicating after about six months. From then on we were pretty much at each other’s throats. And I became very wary of getting into another situation like that, because it was very harmful. I turned responsibilities over to them that weren’t looked after. So I slipped. I lost ground. And I decided to handle my own affairs. I might have done better during that period with a manager, but for me it was essential to have absolutely the right person, or no one at all. “With Silk Degrees I felt very confident of my musical ideas and the record company was giving me very strong support. Don Ellis (head of West Coast A&R) and I go back a long time. He was part of the gang back in Madison; he started off working at Discount Records there. But everyone knew without the right management I wouldn’t have my full shot. And Azoff turned out to be right. “There are only a few managers at his level. Of course it’s all a tricky business. Managers have egos and desires and career moves of their own and any approach between an artist and a manager is a very cautious, very careful courtship. It finally came down to three or four firms in L.A., and the closer I got the more natural it became to work with Irving. We signed in February, 1976, just before Silk Degrees came out. I was firmly resolved not to let the LP be released until I was represented by someone who could handle it right from the beginning.” As for the quantum leap in Boz’s fortunes between Slow Dancer and Silk Degrees Azoff says simply, “He was ahead of his time,” while he goes about putting Boz’s money into oil wells, and Boz goes about experimenting with the creation of whatever 1980’s R&B is going to be. It was exactly that kind of experimentation which made Down Two Then Left such a different album than Silk Degrees. It was not as popular, and it lacked the tunes that jumped out and grabbed people by the ankles like those in Silk Degrees. “That had to do,” says Boz, “with the basic constitution of Silk Degrees and the approach we took to it. We wanted it to be very, very accessible, very refined and very simple. Not complicated, not obtuse… we just wanted to play it right out, obvious tempos, obvious rhythm patterns, obvious energy level with every song having a certain intensity. I wanted an album that would be accessible to a lot of people. I needed that shot in my career. I wanted to sell a lot more records. “Those were not the intentions behind Down Two Then Left. It’s a more complex title, the album had a more complex cover, and the music is more complex. It wasn’t supposed to be easily digestible. It wasn’t easy for me to digest. It was a much longer process in the making. I took it apart and put it together again a thousand times. And I believe it will stand up to that kind of critical listening. It will be around a lot longer than Silk Degrees will. It will bear a lot more listening. I know it does for me. I’m still fascinated by it, I can still put it on and hear things. Silk Degrees hasn’t worn like that. I love doing the material in performance. It’s up, it has that vitality, it’s in a very major vein. Real good stuff to perform. “Down Two is not like that. The vocals are more difficult, for instance. I’d write the song and find that in order to do the kind or lyric or melody lines I’d want to do, I’d have to work in these strange octaves and strange ranges that I was not used to. So the vocals came out very different. There were falsettos and things that sounded strained or out of tune to me, although they weren’t. I tried out some things and I learned an awful lot from making the record. I think it will make the up and coming record a lot easier because I’m a lot more sure about what I can do as a result of going through some turmoil. “Anyway, because it wasn’t as digestible I expected some criticism on it. But I didn’t take the safe path by any means. I could have made another Silk Degrees. There’s no secret to it. The musicians, the producer, the studio were all there. But that would have been boring.” If there is any one thing, says Boz, which has kept him current, kept him from being boring, it is a continuing fascination with the myriad forms of pop music. “I’m continually fascinated by what I hear. All I know is what I hear on the radio, in the car or wherever. That’s all I know about music, that’s how I learned to play guitar. It was fascination with the new disco rhythms which led to some things in my own work. I don’t know anything about disco, really. I know there’s a whole other market out there and that there are people who make records for it. “I don’t go to discotheques very often. Sometimes on tour it’s a good place to go after a show. One night I wandered into this place, 230 Jackson, a place that’s just closed down. The guy was playing some stuff that was way out. Sound, rhythms that really knocked me out. I have an appointment with the guy so he can play me some stuff because I want to find out if it was just that night or the sound system or the lights, or whether the stuff was really that good. “But in general, right now I have to admit that I’m not as fascinated as I’ve been at times in the past. I feel I’m going to regress a bit, go back to some of the beginnings. These days I’ve been listening a lot to Ray Charles and Horace Silver.” It is likely that the majority of the fans who bought Silk Degrees do not know the music of jazz pianist Huraco Silver, but it is also likely that Boz will take the inspiration he finds there – as he has taken inspiration from so many sources – and compose from it more of the soundtrack for the continuing voyage down his “Dream Coast.” Indeed, it might have been his Dream Coast of San Francisco that Boz was addressing, when, on My Time he sang the wistful lines from David Brown’s song, “Slowly in the West”: “Thanks again for your moonlight generousness/Just show me to the ending and forget the rest.”

|

|||||||||

that neighbourhood, making it the principal theatre of action on his “dream coast” – is one of them. He and his wife Carmella – who is expecting their second child in July – are just now coming into the home stretch of redoing the house from doorknob to bedpost, and the care that has gone into every corner is like an unseen but perpetually present guest.

that neighbourhood, making it the principal theatre of action on his “dream coast” – is one of them. He and his wife Carmella – who is expecting their second child in July – are just now coming into the home stretch of redoing the house from doorknob to bedpost, and the care that has gone into every corner is like an unseen but perpetually present guest.