The Dallas Morning News - Boz Scaggs Interview

Boz is back....

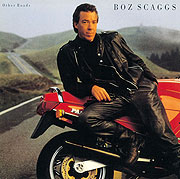

[July 3, 1988]Here's the lowdown on the '70s Grammy-award winner who's taking his show on the roads for the '90s SAN FRANCISCO -- In a lemon-yellow bedroom in a wood-shingled house on a San Franciscan street is a poster of a once-famous rock star. "Boz Is Back!' the neat white letters shout. If you squint, the words look joyous and jubilant. Boz Is Back! Boz Is Back! Boz Is Back! And there he is, William Royce Scaggs -- Boz Scaggs -- staring out from the poster with the Annie Leibovitz photo, looking sexy as ever in tight black leather, his right arm and leg cocked seductively against a lipstick-red motorcycle at an angle that suggests supersonic speed. The title of his first album in eight years, Other Roads, fits right in with the road in the poster, twisting into a emerald horizon of ethereal hills. Here he is again, but this time it's the real life Boz -- unpretentious, kind, polite, generous, gentlemanly -- sitting under "Boz Is Back!', looking like just another 44-year-old in faded black jeans, worn green shirt and leather house slippers. His backdrop is not a glamorous motorcycle but the flotsam of his youngest son's room. A stray sneaker pokes from under the bed. A drawer in a red bureau hangs open. Toys scattered about, plastic dinosaurs and Army trucks, a tennis racket, a flour-and-water relief map of California. The Texas-raised rock star who delivered such '70s hits as We're All Alone, Lido Shuffle and Breakdown Dead Ahead, the celebrity who made millions, whose Lowdown won a Grammy for the best R&B single, who made international headlines, who critics hailed as the sexiest popular singer since Frank Sinatra -- this same man is now a responsible father making a cursory sweep around his child's room, tidying up for the day's interview. Actually, he's not the same man at all. Boz is eight years older than when he dropped out of sight in 1980 with four Top 20 hits and screaming sellout concerts. Since then, he's gone through a bitter divorce from his socialite wife, Carmella Storniola, and fought for joint custody of his two sons, Oscar and Austin. He opened a bar called the Blue Light Cafe in San Francisco and this fall plans to open a restaurant called Slim's. He bought a sailboat and sailed the seas. He went trekking in Nepal. He climbed Mount Everest. He traveled to Sri Lanka, New Zealand, Thailand, Austria and Canada. He went hiking in Switzerland. He kept a motorcycle in Paris and zoomed through the French countryside. He took a lot of walks. He read. He thought. He did nothing in particular. He felt guilty. "When you stop the routine (of making albums), obviously there's still some wheels spinning,' Boz says. "There's still some momentum". "When you're completely inactive, you think you should be doing something. There's some sort of guilt that goes with it. I got over that fairly soon. In about three years, I stopped feeling guilty about not working. But there's still something that's missing. It's like an appendage that's not there. It still itches. It was then that I think I realized that there really was some need, some outlet, that was real basic to my nature that had to be fulfilled. "I didn't know exactly what I was going to do. I think I knew more about what I didn't want to do (musically) than what I wanted to do.' So it was another two years before Boz would actually begin recording Other Roads. It would take three more years to finish it. But then, when he finally gave the album to CBS Records, Boz received a crushing response. Al Teller, then CBS president, "didn't hear a first hit single,' Boz says. They heard hit singles, he explains, but not one stunning enough to promote as an album-seller. "It was just essential that there be a single. It's become singly the most valuable marketing tool that they have.' Teller asked Boz to return to the studio to record another five or six songs. "It was like a slap in the face, and I really wasn't ready for it,' Boz remembers. "I'd never had that said to me. I mean, I turn in my albums, that's my work. I put everything I've got into every moment. I name it, do the cover, turn it in and that's it. Then I'm gone -- I'm on to the next album. I was shocked and humiliated.' For someone who says his truest trait is "stealth' and who values nirvana more than fame, fortune or even love, the fiasco was inconceivable. The only way out was to rely on these two forces of his nature. Back at the beginning, Boz never would have envisioned this. There was no such thing as a rock star, much less a rock star battling an unhappy record company. Because, at the start, music was just music to Boz. And his passion for it was insatiable. ******* The son of a traveling salesman, Boz was living in Plano when his desire surfaced at about age 11. Coincidentally, it was a critical time for the music world. "I loved to listen to music on the radio,' Boz recalls. "That was the beginning of rock 'n' roll, about '55 and '56. Every night, I'd lay in bed with the lights off and the radio next to my ear, going through the stations. I listened to everything. There was a particular station out of Nashville that we could get after a certain hour that had some real obscure stuff we couldn't get in Texas. And of course all that good black radio in Dallas. There was a station called WRR that played re al obscure American roots music, basic blues and stuff. So I was real interested in music. "I loved it. It was like beaming in from some alien planet. It was not something that I really had in common with a lot of other kids in my class at school. There were only two or three that were as tuned in as I was.' Although his early musical heroes were T-Bone Walker, B.B. King and Bobby Bland, it was the Ray Charles experience that transformed him. "I saw him at the State Fair auditorium,' Boz recalls, "with a 90-percent black audience. When I saw him, it just shocked me. It just blew me away. I'd never sat in an audience and seen musicianship like that. Not only Ray's, but the whole band. I was just electrified. "I remember sitting next to a young black woman, I was maybe 14 or 15, and she was probably not more than 16 or 17. At some point during the show, Ray was doing some sort of ballad, and she reached next to me and unknowingly just grabbed my arm and just squeezed it. It was almost bigger than the moment, the music that was going on itself. But the whole audience was just gripped with excitement. It was just a real deep musical and emotional experience. It was like an epiphany. It was probably th at jolt that made me really see myself as pursuing my interest in music and want to be able to do that.' That was perfect timing for a musical epiphany because Boz was attending St. Mark's school in Dallas and had recently met a fellow student named Steve Miller, who had a combo called the Marksmen. Boz already had taught himself some simple folk tunes on a "border special' guitar that he'd bought for $15. Then he progressed to experimenting with some "basic blues' and met Miller who was "playing some rhythm and blues.' Quiet but revolutionary change overtook Boz -- a new nickname, a new band. It was also a time when his stealth began to show. ******* "When I knew him at St. Mark's, he was much more of an outsider,' remembers Lewis MacAdams, now a writer in Los Angeles. "I think he watched the world at St. Mark's until he could find a place where he was a central figure. I think coming from a place like Plano at that time, when it was still a little bitty town -- coming to St. Mark's, which was filled with wealthy kids from North Dallas, he was sort of an outsider. "His nickname was originally a put-down. This guy Don Lively was pretty much a country kid himself, and he was able to spot somebody who actually was from the country, though Boz never seemed like a country boy. Anyway, Don thought, "What's a really weird name?' and he came up with Bosley. Boz was able to stand back and eventually turn the name around.' Bosley became Boswell, Bosworth and then just plain Boz. In the meantime, he found his spot. In 1960, Boz joined Steve Miller's band, doing gigs at country clubs and mixers all over Texas, Louisiana and Oklahoma. After he graduated in 1962, Boz followed Miller to the University of Wisconsin to play in Miller's band called The Ardells. Boz was so consumed by music that he "flunked out' of college. Returning to Texas in 1963, the Vietnam years, he joined the Army reserves for six months, then formed a band called The Wigs. But being a free-spirited "traveler' by heart, Boz hungered for more exotic locales and, by early 1965, he landed in Europe. At first he had a rhythm and blues band, but most of the members soon went home to form Mother Earth. So Boz embarked on cosmopolitan peregrinations during the psychedelic '60s. While his peers were in San Francisco for the Summer of Love, Boz was traipsing through Europe and India working as a folk singer. Oddly enough, the man who would make millions off his music wasn't singing because he wanted to become a rock star. At the time, he considered music -- specifically his ability to play guitar -- "a crutch.' Music was just something that helped him "pay the bills.' "When I needed something,' he explains, "I could play on the street or I could play in a little club. It was just what I did. Other people were writers or painters or truck drivers or whatever they did. I just happened to be able to play the guitar and sing and, you know, entertain sometimes. But I never really fixed on that as being a profession. I also washed dishes.' Boz was something of a purist then. With no real responsibilities, he had the luxury of viewing music as "a meditation, an escape.' But by 1970, back in America, he found himself "with no place to go and nothing particular to do.' He made some calls, got "some guys together' and decided to commit to becoming a professional musician. Then a curious thing happened. "At the point it started becoming a profession,' he says, "it started losing some of its value to me.' It would also make him famous. ******* At the peak of his fame in the disco-fevered late '70s, Boz could do no wrong in the music industry. But after his long hiatus, Boz discovered a lot had changed. Not only were the rules for the entire music industry different, but many executives he'd known were no longer around. Before he dropped out, Boz always had good relations with his record company. Back in the days when he was married, he whipped up Italian pesto sauce in his kitchen as Christmas presents for various executives there. Rolling Stone even commented that he "set some sort of record for actually attending record company conventions. In the process, he became a favorite with the company.' Boz says the company was "great' during his long break. And when he started to work again, he says, "they had left me alone, which is what I wanted.' But then Boz turned in his work, and the trouble began. Boz didn't know Al Teller, the new company president. Teller didn't know Boz. And worse, Teller didn't hear a first single. So Boz -- who had grown accustomed to instant acceptance -- was forced to consider his options. One report told of an offer from Irving Azoff, president of MCA, to release the original version of the album on his label if Boz broke with CBS. But Boz was weighing two other options. He could force CBS to release the album as it was. "They can't refuse. Contractually, I'm empowered to say, "I've done a high-level product, and it's what I do. There you go. Release it.' Or I could say, "OK, I'll cooperate.' ' Which is what he did. "I said, "OK, I'll go back (in the studio).' I said, "I'm not going to just send it till you say stop. I will do this, and when I've done that, that'll be it. I'll cooperate. I'll do my best, OK? We'll keep it positive.' It's life and death, in a way. I was doing it because that's what I thought I had to do.' It had been a long time since Boz did something because he felt he had to. Even when he was traveling through Europe and India, Boz pretty much had free rein with his music. Back then, he could cut an album in a day and become an overnight sensation in Stockholm. ******* Over in that coolly beautiful Scandinavian city in the late '60s, Boz cut his first album, Boz, which was a hit over there but never released in America. Featuring a few Bob Dylan songs, it was mostly rhythm and blues tunes played on an acoustic guitar and a harmonica. Soon after, Boz received a postcard from his old friend Steve Miller, who wanted Boz to join his band in San Francisco. Boz liked the idea, and in late 1967 arrived in the hotbed of psychedelia. He hated it. "I was coming from a different place,' he explains. "I'd just come from Nepal and India. I picked up a Time magazine, and I saw people dressed up in costumes. They looked like cowboys and Indians. It was very American, and I was not feeling very American.' "Boz wasn't a hippie,' remembers Jann Wenner, publisher of Rolling Stone, who then lived across the street from Boz in San Francisco. "He was smooth, sophisticated and elegant.' While Haight-Ashbury teemed with free-loving Diggers and Merry Pranksters, Boz and Miller were hard at work. In 1968, they made two albums -- Children of the Future and Sailor. They were considered one of the hottest headline acts at Bill Graham's Fillmore West. The Rock Encyclopedia calls them the "premier psychedelic guitar band' of that time. Despite their success, Boz stayed with the band for only a year. He says he left because he's not "much of a band personality,' not like musicians who "make their decisions and go their direction as a group.' But others remember a harsher scene than Boz describes. "I know they had hard times,' says a friend who was close to them at the time. "They were always at each other's necks. They'd pull each other's plugs on stage. Maybe that was more Steve's doing than Boz's, but there was some fracas going on.' At any rate, Boz left to do an album of his own that was produced by Wenner, then one of Boz's closest friends. Through Wenner's contacts in the music industry, Boz recorded Boz Scaggs at the famed studios of Muscle Shoals, Ala., with musicians who'd worked with Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett and Percy Sledge. "We were two kids,' says Wenner, "going to the home of this great rhythm and blues stuff. We were kind of scared and intimidated. But it turned out all these guys were young cats, like me and Boz, only they'd been raised in Muscle Shoals.' Wenner got guitar-playing legend Duane Allman to join Boz on the song Loan Me a Dime, which became a high point in both men's careers. The bluesy album earned Boz "instant notoriety,' according to The New Rolling Stone Record Guide. In rapid succession, Boz did another three albums before recording Slow Dancer in 1974. Then two years later, he did Silk Degrees, which would sell 7 million copies and win him the Grammy for Lowdown, the best rhythm and blues song of 1976. When Silk Degrees was first released, Boz was working so hard touring clubs and colleges across the country that he didn't really notice what was happening to the album. "I didn't really look it (success) in the face,' he says. "It was just something that came from a lot of hard work, and it meant that I could keep on working very hard. It was really only well after the event that I could look back on it and see what a phenomenon it was, and what it really meant to me and my career.' Overnight, Boz became an international sex symbol. Newspapers and magazines reported on his charisma, his white silk shirts, the girls who leaped on stage to hand him red roses. After Silk Degrees, Boz did another two albums -- Down Two, Then Left and Middle Man -- and in 1980 he released Hits. But 1980 was a strange year. With four top-20 hits, Boz dropped out of the music world and out of sight. He wanted a break from the "routine' of recording and touring. He wanted to spend more time with his toddler sons. And his eight-year marriage was in trouble. ******* Boz dislikes going into detail about those tough years, but in 1984 he spoke openly with his friend, Ben Fong-Torres, who was writing a story on him for GQ. "We had two children,' Boz told Fong-Torres. "I wasn't happy . . . That was the thing that divided us, as opposed to the way you'd think it would work. I expected certain areas of my home life to be taken care of while I was away, and I found that Carmella was not looking after the home front. She was at the height of her career as well -- her social career.' "Carmella, a bright, stunning woman,' wrote Fong-Torres, "was high on society, and her energetic ladder-climbing was well documented by an adoring black-tie press. Boz, in the meantime, was seen here and there, hosting a symphony benefit or smashing up his motorcycle, attending a ballet performance or getting into a drunken brawl.' Over the following 3 1/2 years, the parents fought for custody of their sons. Boz won joint custody. Today, one of the things that really bothers Boz is reporters who try to paint him as sad or broken-hearted. A recent Rolling Stone article quotes poet Jim Carroll, who contributed some lyrics for the new album, as saying he could feel "an edge of sadness that walks around with him. I think he was carrying a certain weight with him, but I don't know what it was.' "That was an overstatement,' Boz says hotly. "That whole article was an overstatement about hardships and trouble and hard times and sadness.' But if there's no sadness to Boz, there is a certain quiet and spirituality. The most important thing in his life, he says, is nirvana. Music can be a source, he says. Love can't. Nirvana, he says, "is a time and a place. You walk around a corner and see a little red wagon, and it's a perfect photo and it's a perfect smell and it's a perfect day.' This state of "mental ease' just comes in fleeting moments, he admits. But there is hope for more. "I think you can achieve it in a lifetime, and I think there is such a thing as learning to live gracefully. Grace is a state -- a deified state. It's sought for in every religion and every discipline. One time I was talking to a friend of mine . . . He asked me what my nature is, and I said that my nature was stealth. This is a rather odd thing to come up with, but it was the first thing off of my tongue. "I go carefully and very slowly. In other ways, my life is completely haphazard and random. Anything can happen. But in another sense, I take it slowly and watch carefully. I'm always moving from one environment to another. I've always felt that my life's been transitional, from one small town and one small world into a slightly larger world. And that's what I do. I'm always moving carefully to the next stage. Once I'm there, I see my way around and move to the next one.' A student of Eastern philosophy, Boz believes he can get "very close to that state' of nirvana. "I feel confident,' he smiles. "It's a real goal of mine to develop an inner grace and learn how to hold on to it.' In the end, it was these two guiding lights -- nirvana and stealth -- that acted as beacons in the storm of troubles with his album. For "mental ease,' it made sense to make one more attempt to work things out amicably. As for stealth, Boz was moving carefully through this new stage in his life, this return to the mainstream after seven long years. "I was just sort of taking it a step at a time,' Boz says. He did some remixing and added some material that, he says, "in my mind improved the album. I replaced two songs which are not songs that would have made or broken the album. We reworked it, and we finished that in December 1987. They (record company executives) liked it a lot.' So far, public reaction has been lukewarm, but it may be too early to judge how the album will do on the charts. The first single, Heart of Mine, hit 35 before dropping down to 40. The second single, Cool Running, will be released in two weeks. Rolling Stone says it's one of the "album's finest moments,' and the hope is that single will propel Other Roads up from its current position of 47. Music critics already have had their say. "I think that in general it's been a well-received album,' says Jean Rosenbluth, album review editor for Billboard. "We gave it a pretty favorable review.' "What I like is that it's got such diverse styles,' says Sheila Rogers, who reviewed the album for Rolling Stone. "There's jazz, real rock 'n' roll and typical Boz Scaggs love songs.' Still, she is not without reservations. "It's a good album,' she says, "but I don't think it's a great album.' But critics don't make or break an album. "Music critics are not as powerful as movie or theater critics because there's radio,' says Ms. Rosenbluth. "If people hear an album, they'll go buy it regardless of what a million critics say.' Meanwhile, Boz, operating on stealth, is cautiously approaching the next stage of the game: promotion and touring. He's just returned from a publicity tour of Japan where he'll give concerts for two weeks this July. Before that, he was in Montreaux, Switzerland, where there was "a big convening of European press in conjunction with a music show.' Boz is scheduled to tour America from the end of August to the middle of October, with a concert in Dallas scheduled for Sept. 14. But he seems to be putting more effort into press tours abroad. "I'm concentrating on the international more than anything else,' he says. "I'd rather be there.' But getting there takes a lot of work, which is not easy when you have kids. * * * * * * * "He's a good father,' says longtime friend and Dallas entertainment agent Angus Wynne. "He takes the kids to school and really spends a lot of time with them.' "I'm sort of Mr. Mom with them,' says Boz. "I have a housecleaner and a cook, and the cook does all the shopping and prepares the dinner and makes their school lunches. I get up with them in the morning, and then do whatever there is to do after school, homework and sports.' His sons are only "mildly curious' about his role as a professional musician. "They've been aware of my status as a famous person,' he explains, "but now that this album's out they see me in the newspapers and on the television, these posters for the record and all. They know me too well. They're not the least bit impressed.' They should see him now, on this San Franciscan afternoon, shifting into his rock star role. The kids are in school, the housekeeper is cleaning, the cook is shopping, and Boz is manning the phones, madly working out details for the Japan tour. Punching phone numbers, switching from line to line, Boz doesn't even have time to think about hitting the Los Angeles soundstage where he will tape the video for the Cool Running single. Still, he's cool under pressure. "Can you hang on one second?' he says to a choreographer. "Hello?' Boz flips to another line. "Yeah, hi Craig,' he says to his manager. "Can I call you right back?' Back to the choregrapher. "Look, do you know anything about him? Does he sing? He moves great.' "Ummmhmmmm . . . ' "Well, what about her? Did you ask her about her dancing? She feels strong? She feels confident?' Boz wouldn't be under this pressure if not for the Japanese visas. He needs to get the applications to the Japanese promoter by tonight, so he can process them first thing in the morning. It's kind of "blind,' Boz says, calling people and depending on recommendations, but it's the only solution. Besides, there are lots of other things he has to think about. Punch punch punch. He calls someone about a piece of equipment he's experimented with, an earpiece that fits invisibly in the ear and an antenna that hooks around the neck. He calls his manager. He calls his accountant. While talking, Boz plays with a yellow tape measure. His legs are sprawled, the phone is cradled in his ear. He is oblivious to the activity surrounding him. Two men with light fixtures go up and down the stairs with boxes of lights for the bedroom he is renovating. A photographer clears away equipment from a photo session on another "Boz is Back!' story. Somewhere in the background, a baby -- the child of one of his housekeepers -- cries loudly. A vacuum roars. Punch punch punch on the telephone buttons. "Hi, Jerry, how are you? Listen, a couple things. You're going to receive an application from American Express. And you're going to need to write a check for 10K to Club Enterprise this afternoon.' Punch punch punch. "I need a quick piano tune. Do you know anybody who could do that this evening? Punch punch punch. "Hi, it's Boz. I'm calling regarding the vocalist Jean. Just wanted to pick your brain on the matter.' Pine trees are framed in the window behind him. An unread New York Times is at his elbow. His office is filled with pictures of his sons, who will be home in a half-hour. Thirty more minutes until he becomes Mr. Mom again. Punch punch punch.

|

|||||||